How to Fight Crocodiles: On Making It a Battle to Be Remembered

by Yang Vicki

A filmmaker once told me he didn’t believe that there were crocodiles in Singapore.

“Where do they come from?” he challenged, shifting his film camera on his shoulders as we moved quietly down the path of a reservoir park.

“I think they’re native to Singapore,” I gave tentatively.[1]

“I don’t think there are crocodiles here,” the filmmaker asserted, in spite of my protestations about a crocodile named Barney found dead in another reservoir just recently.[2] The line producer laughed, unbelieving.

I didn’t expect to be tussling with Barney’s imaginary croc compatriots when I voluntarily trooped along on this shoot, scenes from which would eventually surface in Daniel Hui’s hybrid docu-film Snakeskin (2014). Admittedly, I was thinking less about the film at first when Daniel said we needed to get on the boardwalk that stretched around a perimeter of the reservoir. We inched across the planks that were just a few inches above a liquid void. No railings. Unlike the rest of the country, no lights.

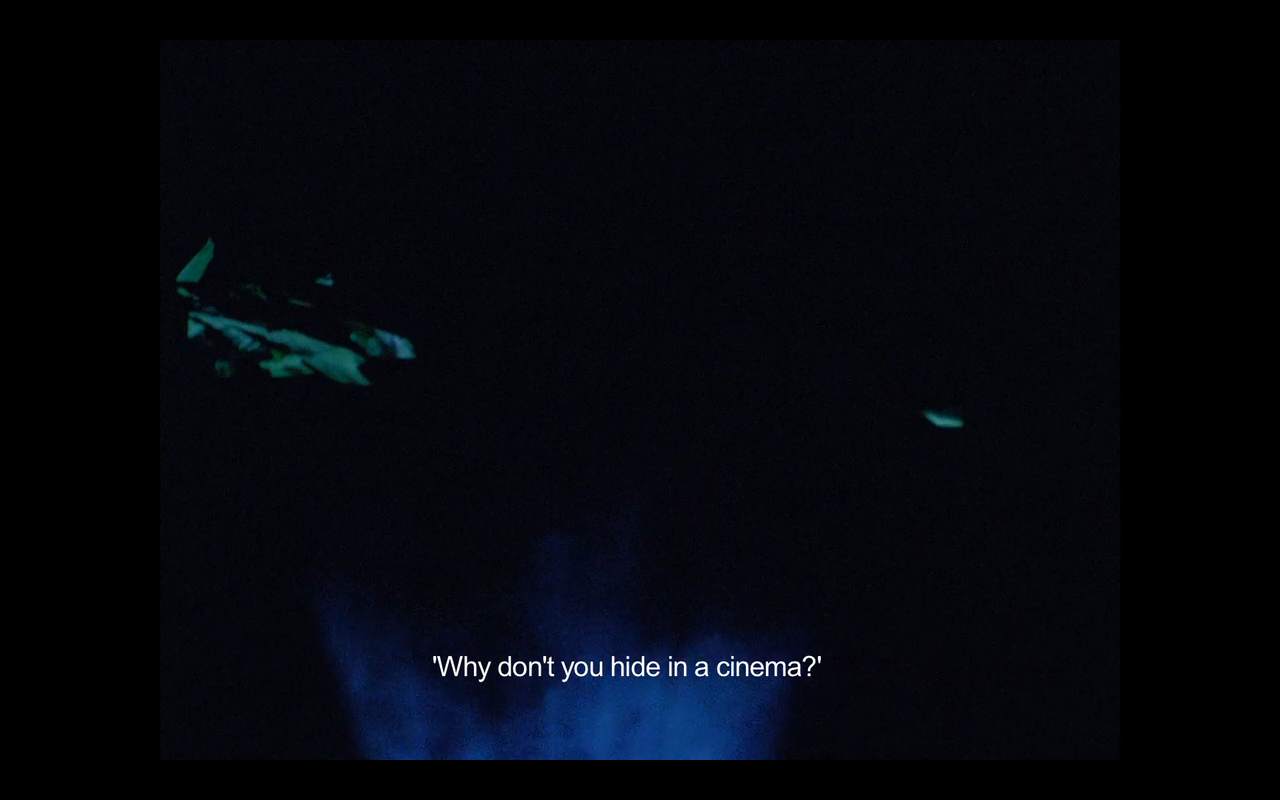

Then there it was—Malayan dancers skimmed and swayed out of Daniel’s rented palm-sized projector and into a Sultan’s court across the reservoir’s waters and against a distant island of trees. I thought if I, as a human, were so impressed, more so would crocodiles be attracted to sudden moving light and life. But I was lost in a daze of ghost dancers emerging from the trees and frames caught in the 1960s and then straight into the gaping jaws of the lake. My spirit was moved, my stomach squirmed.

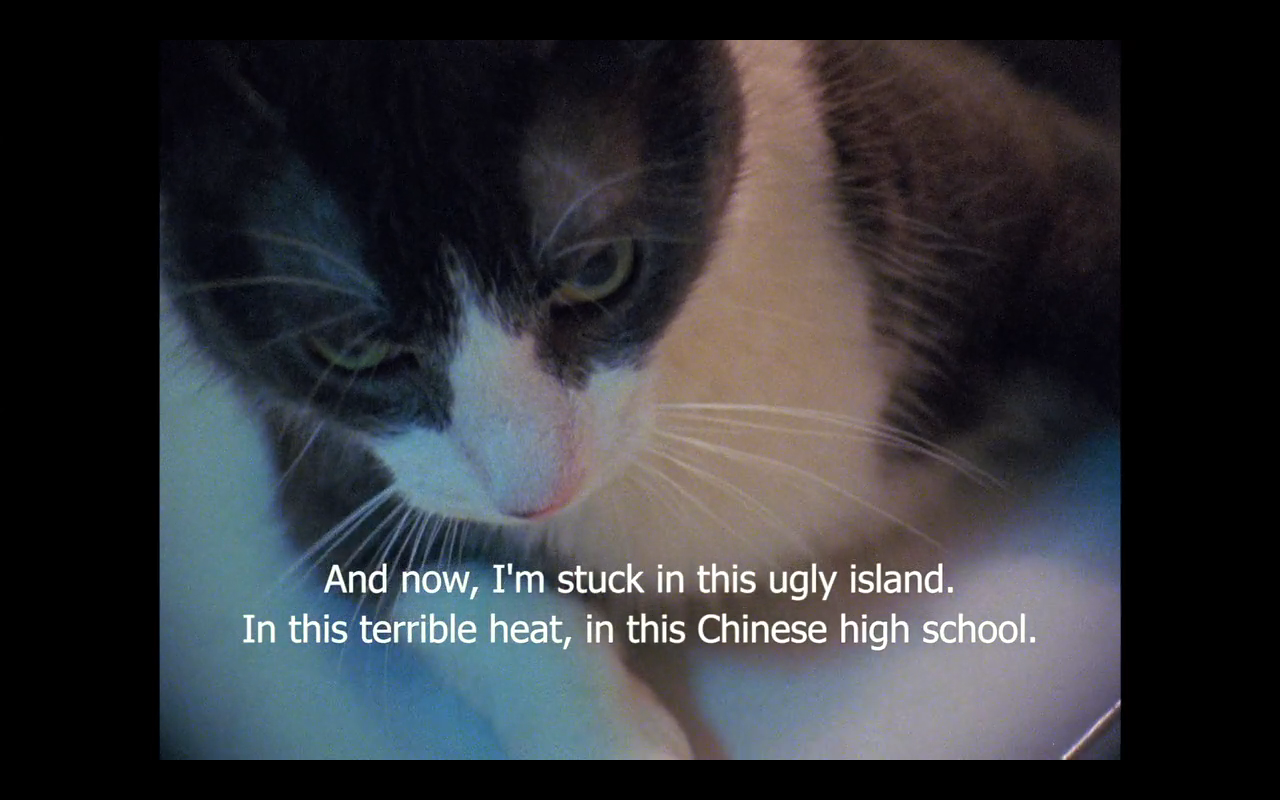

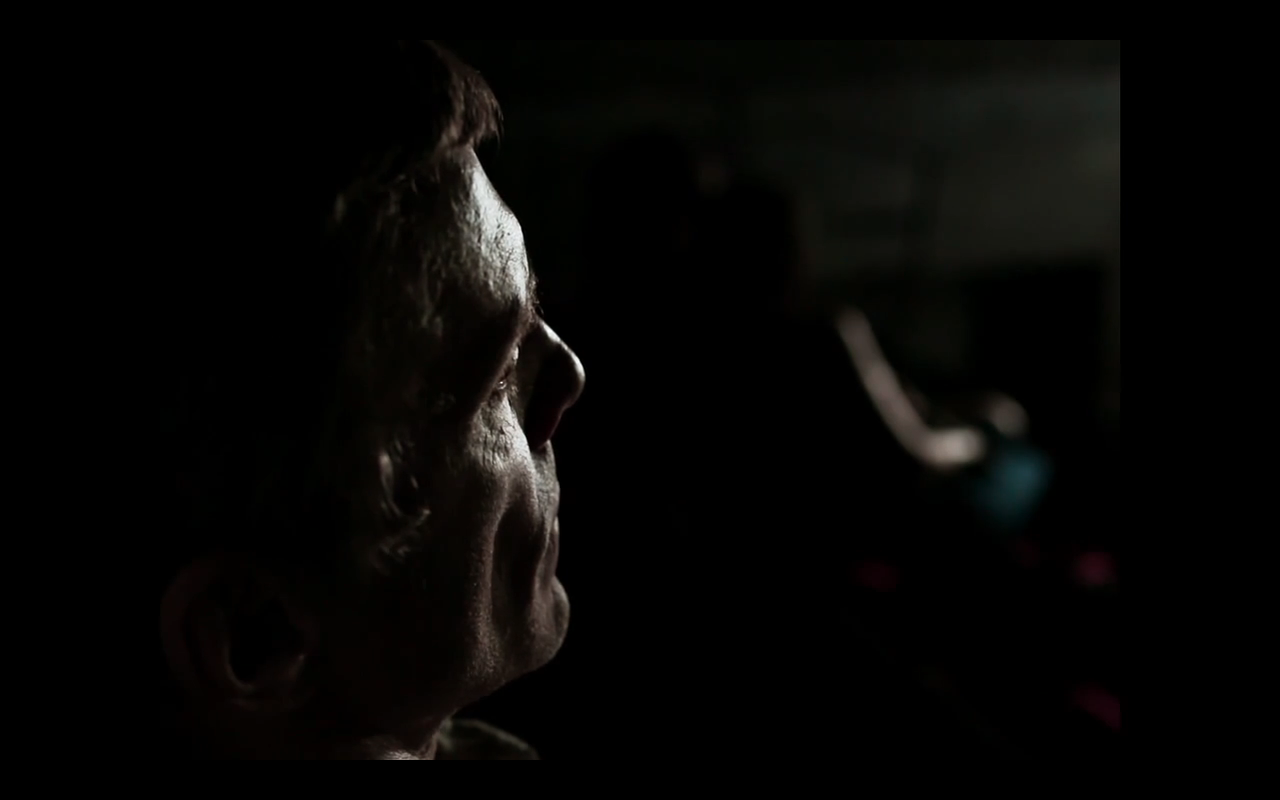

Above & below: images from Snakeskin (Courtesy Daniel Hui)

Months later, what came from our midnight traipse showed itself in Italy at Torino Film Festival. One could barely discern there were dancers in the scene, but the glowing streaks of projected light were stark. Perhaps the dancers were not the point, but rather an indication that they existed. They had been there in the old film Daniel projected in the reservoir and he sought to summon these figures from Malaya and Singapore’s golden age of cinema to the screen again in late 2014. But more importantly, within Snakeskin, they were resurrected in the film’s timeline of 2066.

In Snakeskin’s projection of that era, the dancers or at least the glimmer of them are a resistance against their erasure by an alleged cult leader. Between the starting point of the film in 2014 and 2066, cult and country are conflated by the main narrator of the film, a sole survivor of a cult retracing a country’s events of significance through found footage that its leader wanted destroyed.

The footage unravels a tapestry of narratives, but the stories jump discordantly from one to another, each patiently biding their time to be told. In the film’s line-up of fictional characters and real-life subjects: a cat tells of its previous life as a Japanese soldier during their occupation of Singapore; later, it plays with a historian and activist who recounts the riot against mandatory military conscription in 1954;[3] a young lady (played by yours truly) who visits the historian seems more focused on recalling her old caregiver, Miss Salmah; a film programmer chances upon an old photograph of a woman dancing.

These characters may have different strategies engaging with their own histories but the similarity that arises is their fallible memory. The historian interjects his accounts with probable readings; Miss Salmah’s ward attempts various phone numbers to reach out to her caregiver but spells her name inaccurately. These characters falter at a critical point when remembering and speaking about their memories. Perhaps we can never retell our histories perfectly. Miss Salmah. Shaw Brothers.[4] The Chinese middle school riots.[5] Bukit Brown.[6]

Yet the film’s disparate arrangement of these half-told accounts indicates our dependence on these wispy personal retellings and musings when it comes to laying down a national history on record. The very making of Snakeskin itself, too, seemed a remarkable political exercise, a genuine enactment of a collaborative cinema and a reflection of our reality. There was no script and the non-actors were let loose with few directions. What Snakeskin gave its players was agency. We could tell these stories on our own, with our own voices.

When I watch Snakeskin today, there I see all of us and our personal histories laid out anachronistically by an editor’s deliberate hand. That is how our history has been too—a myriad of voices out of order, confusing and chaotic, but Snakeskin makes them ring with an urgent clarity. After all, whether in 2014 when the film was made or in the envisioned future of 2066, Snakeskin posits an eternal scenario where cult leaders and ensuing political victors desire to burn these voices and narratives to ash.

So how do we resurrect them into reality, into 2019 or 2066? Using the same tools as our ancestors—homo sapiens and rulers alike—Snakeskin offers a destructive baptism of fire so we may reconstruct the myths of our masters. “It is the same fire today that we can use to burn down history. And if we stare into the fire long enough, we can see time. All the years that have gone by. All the memories that we have forgotten,” opines the narrator. And to wrest control of these myths is to change history at their point of beginning.

This suggestion by the film takes us to its ending—and a meetup with a time-travelling character. What did he achieve, what history did he change or so he claims? We do not know but each of us must do the same in our time and headspace, with our own fires of conscience. Displace the current victors by grabbing our own torches.

What will we become without such cinema? Snakeskin lays this out with shots of a cinema audience that may as well be us. We watch this captive audience watching a film, without ever knowing what it is. We can only see the flicker of the images on their impenetrable countenance, the quiver of movement lost in the swaying reservoir trees, the light of cinema.

Snakeskin makes events things to be remembered, whether an innocuous photograph of a dancer or how P. Ramlee gave famed lyricist Yusnor Ef his name, or the riots of young generations, lest those who wield public narratives of history remold them into a trajectory that leads from a prophet and colonizer to their present rule. No matter the persistent erasure of memories, no matter the cult leaders that tell those who remember to jump into the fire, there will be and should always be people and a cinema that remembers. The film Snakeskin itself is evidence and a record of this resistance and lasting fight. It details a battle for the making of history, whether in 2014, or between 2019 and 2066.

*

In 2015 the film was allowed a one-time screening in a small-capacity venue, programmed by the Southeast Asian Film Festival and organized by the Singapore Art Museum. Until a classification rating was given by the Board of Film Censors, tickets could not be sold, limiting marketing efforts. The rating—NC16 (some mature content)—limited the audience to adults over sixteen and was given just a day before the screening date, with no clear reason given to the exhibitors for the delay and the nature of the advisory. Perhaps there were crocodiles we couldn’t see lurking in the depths.

As long as cinema (and art more broadly) has power, so too will it have its predators. I am eternally grateful to have partaken in this film not just as a non-actor, but a player in Daniel Hui’s cinema, a subject in this audio-visual record, and as a Singaporean in a menagerie of myths. This is his film, but also ours—all who are born from the struggles of Malaya, the Japanese Occupation, the riots of before; all who are heirs of a golden cinema age; all who struggle with history and who are caught up in its erasure.

May our memories live longer than the cinema is needed to remind us of them.

[1] Estuarine or saltwater crocodiles are indeed native and endangered creatures found in the wild in Singapore.

[2] Barney was a saltwater crocodile named and well loved by anglers at Kranji Reservoir, Singapore. It was found dead there on April 18 2014. It weighed 400 kilograms and measured 3.6 meters long at time of death. It is suspected that Barney was murdered by poachers.

[3] On May 13 1954, hundreds of Chinese students assembled and marched in protest against mandatory military conscription by the British colonial government in Singapore. The riot police attempted to disperse the assembly with force, leading to violent clashes.

[4] Malay Film Productions was a studio set up by Shaw Brothers in Singapore in 1947, which would go on to launch the careers of film stars such as P. Ramlee and Aziz Sattar as well as lyricist and songwriter Yusnor Ef. The studio was a driving force for the region’s Malay film industry and heralded the golden age of Malay cinema in the 1950s and ’60s. It ceased productions in 1967 after producing 159 films.

[5] The Chinese middle school riots were sparked by the attempted deregistration of the Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students’ Union in 1956, which the government thought was an organization for the communist front. Chinese students across Singapore protested and demonstrated when the schools were ordered to expel some of the students and ordered to be shut down. This further led to an island-wide curfew and police raids on pro-communist unions.

[6] Established in 1922, the Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery holds the burial grounds of early Chinese immigrants to Singapore, including notable historical figures. In 2011, the government announced plans to demolish part of the historic cemetery and exhume its graves to make way for a new road, angering heritage advocates and conservationists, civil society groups and members of the public. The cemetery was placed on the World Monuments Watch 2014, which records threatened international cultural heritage sites.

Yang Vicki has been trying to contribute in meaningful ways to cinema in the last decade—on the page but also on- and off-screen and to films including Demons (2018), A Land Imagined (2018), and Snakeskin (2014). Vicki has written for National Museum’s Cinematheque Quarterly and Asian Film Archive. She is the co-founder of the online magazine POSKOD.SG and the mastermind behind COCKEYE—the silliest zine on cinema in the country. http://yangvicki.com.