Behind the Flickering Light: The Archive and the Amateurs

by Umi Lestari

The 1998 Indonesian Reformation, aka the “Post-Soeharto era,” opened many possibilities. However, behind the openness of the media, behind the flickering light of the film festival opening night or film premiere, people forget the important foundational pillars in Indonesian cinema: the archive and the amateur. Sinematek Indonesia, the first film archive in Southeast Asia, looks more like a “celluloid grave” nowadays. While there are several initiatives to restore film, people hardly ever see the result, and the organization is largely unmanaged. On the other hand, the amateurs, who worked to master the technology of filmmaking and then adapted it to the tropical environment, have been marginalized.

Amid the spotlight on Indonesian cinema, Forum Lenteng (a non-profit cultural center and screening space in Jakarta) offers two films that talked about the forgotten archives. The first is Anak Sabiran: Behind the Flickering Light (2013), directed by Hafiz and with Fuad Faudji and Mahardika Yudha as the researcher and the assistant directors, and Syaiful Anwar behind the camera. The second one is Golden Memories: Petite Histoire of Indonesian Cinema (2018), directed by Afrian Purnama, Mahardika Yudha, and Syaiful Anwar. Anak Sabiran tends to talk about the rise and fall of Sinematek Indonesia in terms of linear storytelling. The non-linear Golden Memories discusses home movie archives taken by amateurs from the colonial era up to the present-day in Indonesia. The three filmmakers fly from the Netherlands to Jakarta, then visit Jatipiring, a small city near Cirebon.

The Archive

Misbach Yusa Biran, the main character in Anak Sabiran, is the founder of Sinematek Indonesia. During the 1960s and 1970s, he was active as a director but left it to establish the Sinematek in 1975. Besides that, Misbach wrote the most influential book in Indonesian cinema, Making Films in Java: 1900–1955 (Komunitas Bambu and Jakarta Arts Council, 2009).

If biographical films tend to mythologize their main characters, Anak Sabiran goes beyond that. Hafiz shows Misbach as the Sisyphus who works on the archiving project for more than 40 years. Through Misbach’s journey from his residence in Bogor to the Sinematek in Jakarta, I can see a different portrayal of Misbach: A lonely old man lamenting the past and asking us to save Sinematek Indonesia.

Archives are never neutral. There has always been an ideological battle over their presence. Through conversations in the yard or in the car, Hafiz emphasizes such arguments. When the tragedy of 1965 happened, it contributed to the New Order government (1966–1998) scapegoating the leftists. Misbach tells how the New Order burned the films that were believed to show a leftist ideology. The impact has been significant. As part of the current generation who grew up after Reformation, I could not access the rich culture that was depicted in the lost films made by the leftist-affiliated filmmakers. In addition, there was also an impact on the writing of Indonesian film history, where the names of the right-affiliated figures tended to stay in the spotlight.

Not content with emphasizing the wounds in Indonesian cinema, Hafiz also shows heart-wrenching images. When a concerto in D minor, written by Jean Sibelius, is played along with the image of scattered scrapbooks in a storage room or the image of dried out and broken celluloid, I felt threatened. What if the archive is untreated and possibly lost in the future? What will happen to Indonesian cinema without being able to demonstrate its strong foundation? This is the new war we are facing right now. The Portuguese, English, the Dutch, and Japanese are the past enemies, as we have always been told by the Indonesian history textbooks. Meanwhile, Anak Sabiran shows that our enemy comes from inside. It could result from mold, humidity, or lack of facilities to maintain the archive.

The Amateurs

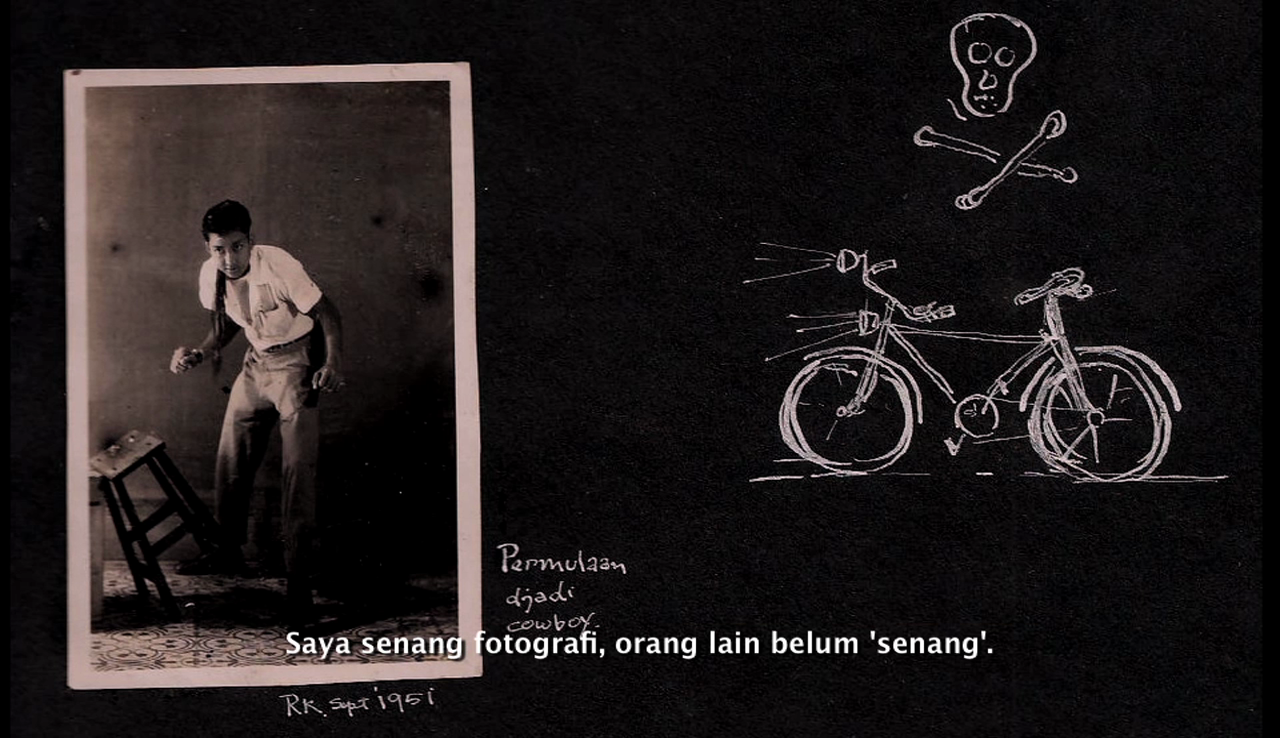

Golden Memories is an effort to embrace the home movies that were marginalized in the film discourse in Indonesia. Home movies can be seen as the authentic archives about family, a small unit in the state, and the proof of how our culture developed, from the perspective of the common people. Right now, we see lots of home movies in social media because it is easier to record with a digital camera. But back then, in Indonesia, it was only those who could afford to buy the camera that could produce home movies. There are two amateur filmmakers in Golden Memories: (1) Kwee Zwan Liang, the owner of sugar factory in Jatipiring who records with Cinekodak from 1927–1940; (2) Rusdy Attamimi, a Garuda pilot, who recorded with a Super 8mm camera.

Kwee is not only recording his family members, but also important guests invited by the Dutch government. One of these special guests was the king of Siam. Golden Memories used the “only showing, minimum telling” method. The reason why Kwee’s family needed to be relocated to the Netherlands is not really made clear. But based on findings by Peter Post, a researcher, Kwee’s family had a privileged status given them by the Dutch. I assume that during the 1940s, Kwee was forced to go to the Netherlands. At the same time, the Dutch also brought their colonial archive and Kwee’s films. Kwee’s films were kept in the EYE Museum Institute, Amsterdam.

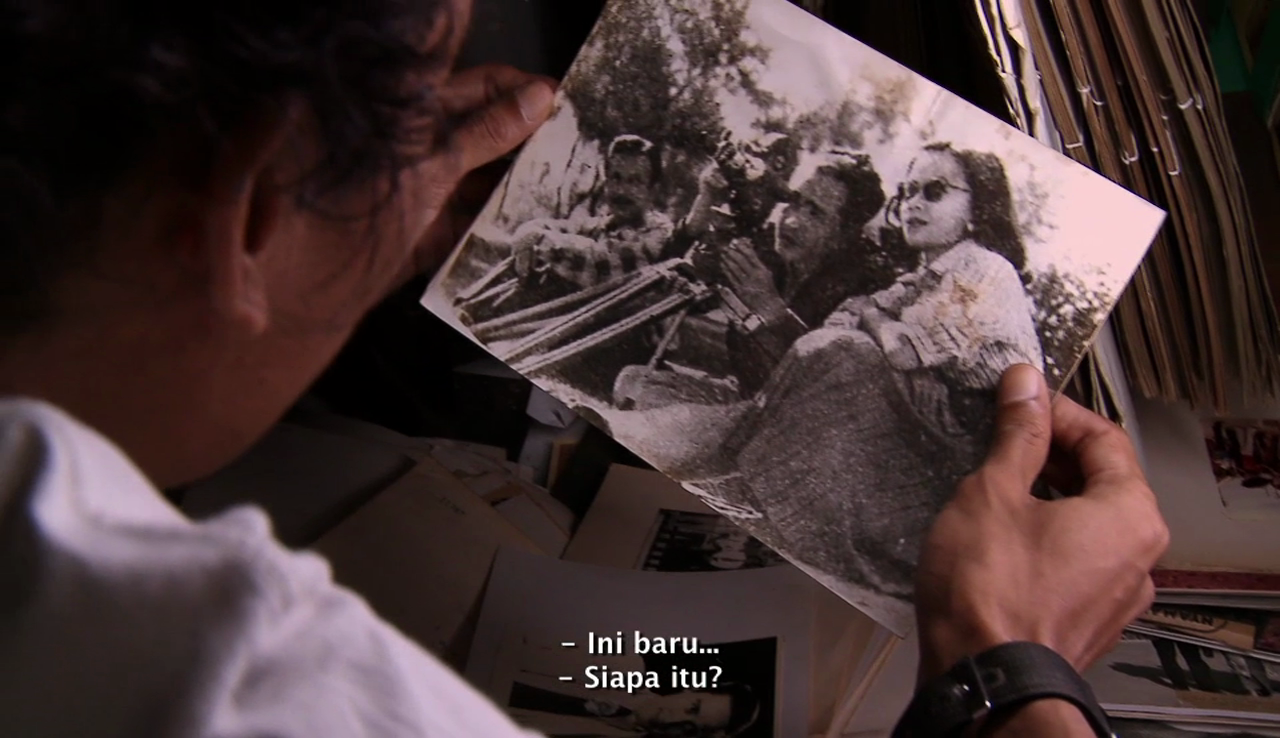

Golden Memories translates the aesthetics of home movies, capturing vernacular things in our daily lives. Conversations with Kwee’s daughter and sons in the Netherlands take place around the dining table. The family shows Kwee Zwan Liang’s film about his children. “There were three colors in the flag. The blue one was still there,” says Kwee’s daughter, pointing out the image of herself through Kwee’s lens.

Besides Kwee, there is Rusdy Attamimi, who started to make home movies in 1963. The most interesting is Rusdy's footage that he took from the cockpit of the plane. We can imagine how the Indonesian landscape must look like from above. In addition, other footage is quite political. Rusdy shoots a demonstration against the war that might take place abroad. Even though he is 80 years old now, Rusdy is still studying the restoration and digitalization of celluloid films. As an independent learner, Rusdy also shares his knowledge: more options are needed for scanning—more expensive machines or more affordable tools.

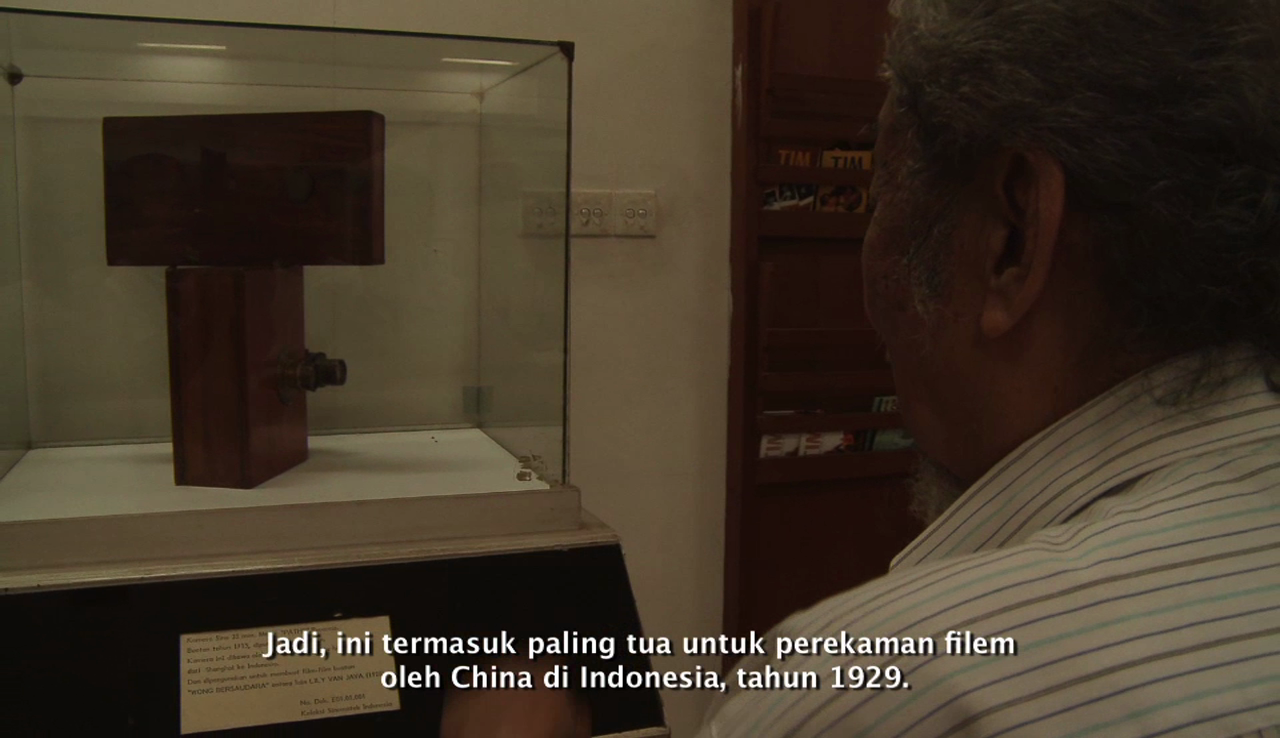

Kwee and Rusdy are only two names from the list of amateurs in Indonesian cinema. I remember the story of Louis Talbot, a French photographer who brought Lumiere’s films to Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1896. Talbot had to deal with humidity and the heat in the Dutch East Indies. Because of the tropical heat, sparks set fire to his studio and burned his recordings of the Batavia streets.[1] Another amateur is The Teng Chun. He made the first film studio and invented a sound camera to avoid the high prices involved in importing sound cameras from abroad. The was also a director who made films based on local stories.[2]

*

As part of the generation who witnessed the growth of Indonesian cinema and at the same time realized that people forget their basic roots, how do I feel? Certainly Anak Sabiran, which shows a room full of celluloid stacks as the poetic landscape for the lonely old man, Misbach, as the Sisyphus, can be seen as an invitation to create a strategy to preserve the archive. We are fighting against time. It could be that in the next twenty years, Sinematek will be completely forgotten and will have no power to haunt the next generation. What is needed now is to distribute the film archive and reframe it.

Golden Memories, with its more fluid aim, actually presents an effort toward reconciliation: Embracing what was never written in the history of cinema in Indonesia. In addition, this film also reminds us that Indonesia still has much work to do. With the massive Indonesian film production scope today, sometimes we forget that we do not have a shared database to archive post-Reformation films in Indonesia. In addition, the statement by Rusdy Atamimi at the end of the film, which confirms that we are independent learners, is actually quite interesting as a way in, to look at the dynamics of Indonesia film aesthetics.

[1] Dafna Ruppin, The Komedi Bioscoop: Early Cinema in Colonial Indonesia (Leicester: John Libbey Publishing Ltd., 2016), 43.

[2] Based on the recording of The Teng Chun interviewed by Misbach Yusa Biran and Salim Said May 24, 1971. This interview appears in the opening of Golden Memories.

Umi Lestari is a writer, researcher, and film critic. Her research explores Indonesian film history and aesthetic and the potentiality of the act to preserve the archive. She is currently teaching in the Film Department at Universitas Multimedia Nusantara, Indonesia. http://umilestari.com/